Ancaman Mikroplastik: Bagaimana Plastik Mengganggu Lingkungan dan Kesehatan Kita

Plastik telah menjadi bagian tak terpisahkan dari kehidupan modern. Sejak digunakan secara luas setelah Perang Dunia II, plastik kini hadir di hampir setiap aspek kehidupan: dari air minum, lahan pertanian, hingga rak dapur rumah tangga. Kemudahan dan ketahanannya menjadikan plastik bahan utama dalam berbagai kemasan seperti kantong belanja, botol plastik, wadah makanan, dan pembungkus produk.

Namun, ancaman terbesar dari plastik bukan hanya dari bentuk yang kasat mata—melainkan dari bentuk mikroskopis yang dikenal sebagai mikroplastik.

Apa Itu Mikroplastik dan Mengapa Berbahaya?

Mikroplastik adalah partikel plastik berukuran kurang dari 5 milimeter yang berasal dari pecahan plastik besar atau dari produk sintetis seperti pakaian. Meskipun kecil, dampaknya sangat besar.

Setiap kali mencuci pakaian berbahan sintetis—yang mencakup sekitar 60% tekstil pakaian—mikroplastik terlepas ke saluran air. Meskipun instalasi pengolahan air menangkap sekitar 95% partikel ini, jutaan mikroplastik tetap lolos ke sungai dan laut.

Lumpur hasil pengolahan air limbah sering digunakan sebagai pupuk, sehingga mikroplastik juga mencemari tanah pertanian, dan masuk ke dalam rantai makanan kita.

Mikroplastik Masuk ke Tubuh Manusia: Lewat Makanan, Air, dan Udara

Penelitian menunjukkan bahwa mikroplastik bisa masuk ke tubuh manusia melalui:

Udara yang dihirup

Air minum (termasuk air keran)

Makanan laut

Produk olahan seperti garam laut dan bahkan bir

Beberapa studi bahkan menyebutkan bahwa rata-rata orang bisa mengonsumsi hingga 5 gram plastik per minggu—setara dengan satu kartu kredit.

Dampak Mikroplastik terhadap Kesehatan Manusia

Meski riset masih berlangsung, mikroplastik dan bahan kimia berbahaya yang terkandung dalam plastik seperti BPA dan phthalates telah dikaitkan dengan gangguan:

Sistem pencernaan

Sistem pernapasan

Sistem hormonal dan reproduksi

Sistem imun

Risiko kanker dan gangguan kesuburan

Dampak Mikroplastik pada Ekosistem dan Hewan Laut

Mikroplastik mengganggu siklus hidup hewan laut. Partikel ini tertelan oleh plankton, lalu berpindah ke ikan, kerang, dan hewan laut lainnya yang akhirnya dikonsumsi manusia. Paparan ini tidak hanya mengancam populasi laut, tetapi juga mengganggu rantai makanan global.

Apakah Daur Ulang Plastik Solusinya?

Daur ulang hanya menyelesaikan sebagian kecil masalah. Faktanya:

Hanya sekitar 5–6% plastik yang benar-benar didaur ulang

Banyak plastik sulit diproses karena perbedaan bahan

Kualitas plastik menurun setiap kali didaur ulang

Simbol daur ulang “chasing arrows” sering menyesatkan; hanya plastik tipe 1 dan 2 yang umum didaur ulang

Kebingungan ini menyebabkan “wishcycling”, yaitu kebiasaan memasukkan barang yang tidak bisa didaur ulang ke dalam tempat sampah daur ulang. Ini justru menambah beban sistem daur ulang dan berisiko merusak peralatan.

Solusi Praktis: Kurangi, Gunakan Kembali, Baru Daur Ulang

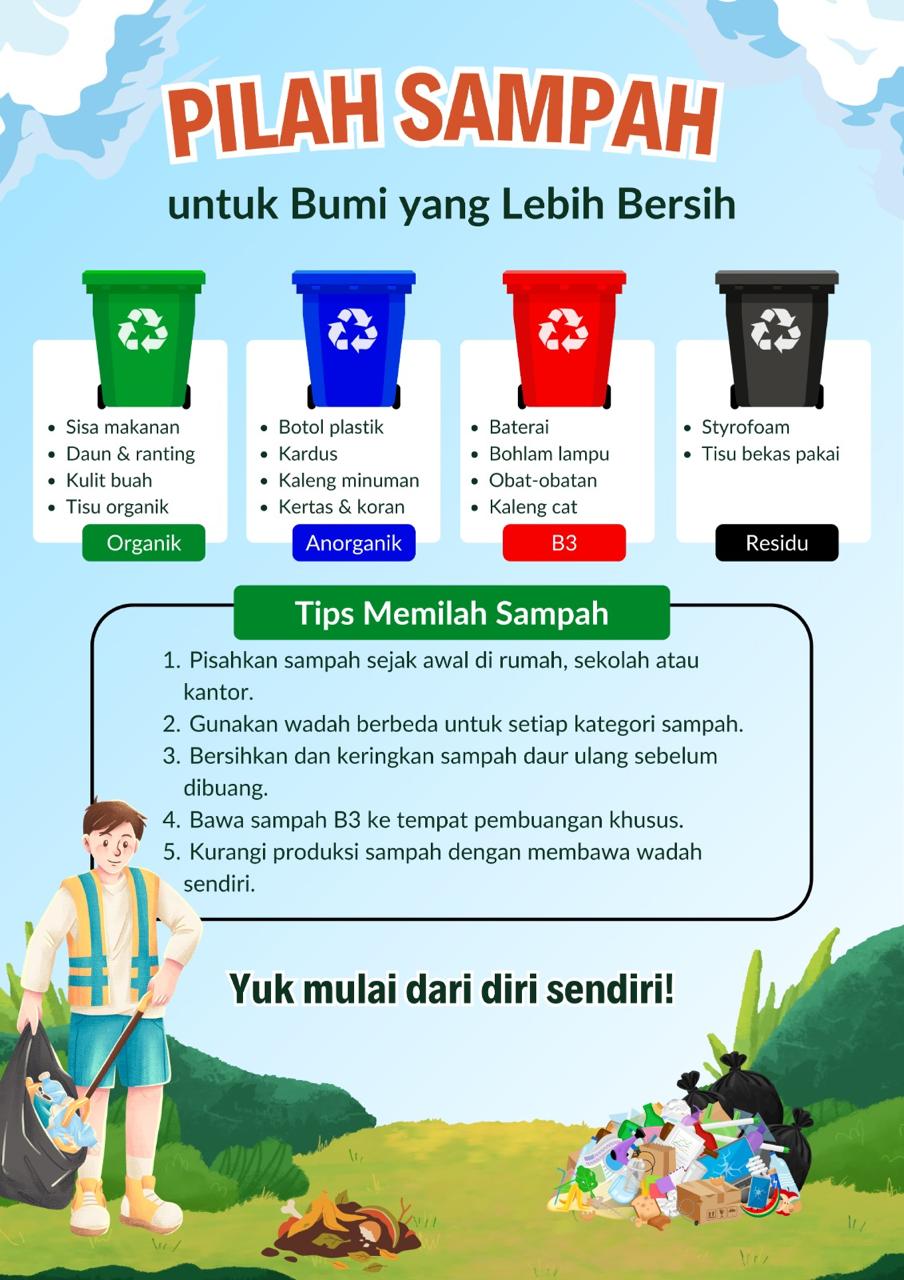

Prinsip “reduce, reuse, recycle” (kurangi, gunakan kembali, daur ulang) tetap menjadi panduan terbaik:

Kurangi penggunaan plastik sekali pakai sebisa mungkin

Gunakan kembali barang plastik yang masih layak pakai

Daur ulang dengan benar, sesuai petunjuk pusat daur ulang lokal

Terapkan prinsip “precycling”, yaitu memilih produk berdasarkan kemasan yang bisa didaur ulang